Boredom and its discontents (Part II)

Amusement parks, crowd control and load-balancing

In Part I, I opened the with news that Disneyland Paris is getting rid of its Fastpasses in favor of a per-ride, per-person premium to skip the line, and explored the history of Disney themeparks and what they meant to Walt Disney.

What we talk about when we talk about themeparks

The long-lost original Disneyland prospectus introduces a place you visit for the simple pleasure of enjoying an immersive built environment, as well as a collection of rides and amusements. It’s a vision of a place you go, as much as activities you do.

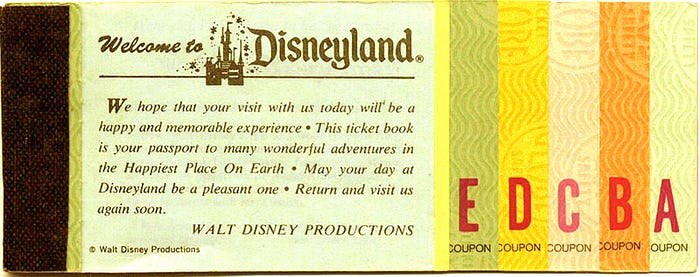

That wasn’t mere aspiration: it was embodied in Disneyland’s inaugural business-model. Entry to the park in 1955 was $1.00 ($0.50 for kids), but this did not include any of the rides. To board the rides, you needed to buy a $2.50 ticket book, which included eight tickets. But your $2.50 didn’t get you any eight rides. Disneyland’s 33 rides were each classified by how intense or desirable they were, with the least intense rides grouped as “A-Ticket attractions” and the most daring thrill-rides classed as “C-Ticket attractions” (“D-Ticket” attractions were inaugurated the next year, while “E-Tickets” were born in 1958).

Ticket books allowed Disney to both set expectations among visitors and manage its crowds. The 1959 “Big Ten” ticket book retailed for $3.50 ($3 for “juniors” and $2.50 for kids) and included one A-Ticket, two B-Tickets and two C-Tickets, and three D-Tickets and three E-Tickets.

By unbundling admission from the rides, Disney was telling guests that admission itself was a worthwhile reason to come to the park. You might come just to watch the strolling players perform live music or sketches; or watch the psychedelic spectacle of a sunset over Tomorrowland, see a parade, or browse the shops or eat a (remarkably small, by modern standards) bag of popcorn.

Likewise, by not unbundling rides themselves, Disney was telling visitors that the rides were like courses in a prix fixe menu: choose your amuse-bouche (A-Ticket rides included various vehicles from the foot of Main Street, USA to the entrance to Sleeping Beauty Castle, including a vintage omnibus, a horse-drawn trolley, and a rotating selection of other historical vehicles); then a couple of appetizers (B-Tickets got you onto the Alice in Wonderland, or into the Main Street Cinema, etc; C-Tickets were good for the Rocket to the Moon, the Mad Tea Party, etc); and onto a main course (D-Ticket rides included the railroad around the park, the Mark Twain steamboat, Storybookland Canal Boats, and more); and finally desert (E-Tickets included the Matterhorn Bobsleds, the Jungle Cruise, and the Submarine Voyage).

The implicit message of the ticket book is that “A good day at Disneyland is ten rides,” and also “Disneyland’s 30+ rides should not all be visited on the same day,” and also, “Every ride has its place.”

Establishing that a “Day at Disneyland” involved riding only one third of the rides, and only two out of the eleven E-Ticket rides kept the lines relatively short, created demand for live entertainment and scenic vistas. That meant that Disneyland’s total capacity was very high — Disneyland could “entertain” a very large number of people, provided those peoples’ definition of “entertainment” was capped at ten rides per day and encompassed contemplative pauses.

Knott’s Gambit

Disneyland wasn’t the first themepark in Orange County. Fifteen years before Disneyland opened, Walter Knott broke ground on a “Ghost Town” attraction to entertain people waiting to eat at the restaurant he’d opened at the family farm. Knott’s Berry Farm is still in operation, and while it is vastly overshadowed by Disneyland, it is intimately bound up in the history of Disney’s approach to admissions and rides.

By the time Disneyland opened, Knott’s had a full-fledged themepark of its own, with free admission and ticket-booths outside of each ride where you paid for admission (similar to a county fair midway today). But in 1968, Knott’s fenced in its rides and began charging for admission, and selling lettered ticket-books that were clearly inspired by Disneyland’s.

Knott’s steadily lost ground to Disneyland, and in 1981, it did the unthinkable: switched to a single-price, all-you-can-eat entrance package. Disney was pressured to do the same, offering visitors the choice of ticket-books or all-you-can-eat admission also in 1981. By 1982, the ticket-books were gone.

The end of ticket-books marked a dramatic shift in the meaning of a day at Disneyland. For a generation that had been raised on periodic, “incomplete,” visits to Disneyland whose texture was informed by the contrast between A-Tickets and E-Tickets, the advent of a one-price admission, priced higher than the combined ticket-book and admission it replaced, transformed the meaning of a “day at Disneyland.”

The food is terrible and the portions are so small

Every time you spend your money, you have to ask yourself whether you’re “getting your money’s worth.” Disneyland’s ticket-books neatly demarkated what your money’s worth was: ten rides. You could “leave some money on the table” by skipping the horse-drawn trolley down Main Street, but that was small potatoes.

Implicit in the all-you-can-eat admission price is that you haven’t gotten your money’s worth until you’ve “done everything” (or, at least, “done all the good things”).

Paradoxically, the higher upfront price of an all-you-can-eat admission didn’t deter the Disneyland crowds, who kept coming in mounting numbers. In the absence of ticket-books, there was no reason not to just queue up for “big” E-Ticket rides over and over.

Those lines soon stretched to impossible lengths, and riding an E-Ticket ride required a willingness to wait for a very long time. This split E-Ticket riders into two groups: regulars who just wanted to get their bones rattled on a thrill ride over and over again and were willing to wait forever to make that happen; and first timers who wanted to know what all the fuss was about.

The first group felt increasingly cheated: they’d paid for all-you-can-eat admission but they were spending all day in line. The second group were just mystified —having waited two hours for their first ride on Space Mountain, they were left asking, “Why were all those other people willing to wait so long?”

Dropping per-ride tickets bundled into ticket books gave Disney a new crowd-control challenge. Their “solution” created an even bigger challenge — tune in next week for Now you’ve got two problems.

Cory Doctorow (craphound.com) is a science fiction author, activist, and blogger. He has a podcast, a newsletter, a Twitter feed, a Mastodon feed, and a Tumblr feed. He was born in Canada, became a British citizen and now lives in Burbank, California. His latest nonfiction book is How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism. His latest novel for adults is Attack Surface. His latest short story collection is Radicalized. His latest picture book is Poesy the Monster Slayer. His latest YA novel is Pirate Cinema. His latest graphic novel is In Real Life. His forthcoming books include The Shakedown (with Rebecca Giblin), a book about artistic labor market and excessive buyer power; Red Team Blues, a noir thriller about cryptocurrency, corruption and money-laundering; and The Lost Cause, a utopian post-GND novel about truth and reconciliation with white nationalist militias.